To Stay in the Room: What Buddhism Taught Me About Euthanasia and Love

Euthanasia is not a Buddhist practice. While the term and modern medical framing of euthanasia are Western, the human impulse to relieve suffering by ending life appears across cultures. What is distinctly Western is the legal and institutional normalization of the practice. In contrast, Buddhist ethics approach suffering not as something to erase through death, but as a condition to understand and transcend.

This essay is not a policy argument or a judgment of others’ choices. It shares a religious perspective rooted in Buddhist texts, conversations with scholars, and research.

In Buddhism life is sacred. The first precept of Buddhism is not to kill or harm another life. This makes the idea of euthanasia fundamentally problematic within Buddhist ethics as it goes against the first precept of Buddhism.

Perhaps more popular versions of Buddhism would state that euthanasia is acceptable if it is not done with the intent to end a life but to alleviate suffering. Intent, is it argued, is the relevant yardstick. This line of thinking is advanced as allowing the ending of a life if your true and undiluted intent is to alleviate suffering, with the ending of a life only being a consequence of this intent.

A classic example appears in the Skill‑in‑Means (Upāyakauśalya) Sūtra, where a bodhisattva ship captain kills a would‑be murderer to save five hundred passengers and to spare the attacker from catastrophic karma. Crucially, the bodhisattva acts without hatred or self‑interest, sees the karmic results clearly, and accepts the karmic cost. These stories are presented as extraordinary exceptions by extraordinary beings, not as permission for ordinary practitioners to break the precept.

Traditional Buddhist texts caution, that even when an act of killing arises from compassion, it still generates karmic consequences for ordinary practitioners. The few Mahāyāna stories that describe “compassionate killing” involve enlightened bodhisattvas, beings free from delusion. For everyone else, intention mitigates but does not erase karmic results.

Two problems arise with the view that euthanasia alleviates suffering. First, whose suffering are we ending? We ourselves suffer when we see the suffering of those we love. How can we know that at some level, not having to see this suffering is a partial motive?

It is a relief to not witness or live with suffering. Buddhism points out that motives are rarely pure. Recognizing mixed motives is not moral failure but insight. The discomfort of seeing suffering mirrors our own fear of decay and death but working with that discomfort can itself be a path of practice.

If the suffering we witness is profound or involves the caretaking of a suffering dog or elderly parent, it also makes us suffer. It is difficult to witness. How many people and cultures place their elderly in nursing homes because it is extremely difficult to care for the elderly in their own homes? Caring for a parent with Alzheimer’s or dementia at home is also incredibly difficult, I know this firsthand having seen my father live with this disease for 7 years. I was relieved to have a caregiver and know that he was living somewhere else. When I decided to take care of my mother with dementia and limited mobility in my own home, I realized just how difficult and all-consuming this type of caregiving actually is.

Is there not some relief in having someone else handle it? Of course there is. In not seeing it every single day, morning through night? In not having to manage the grubby details of memory loss and old age and the dignity that it robs is a relief. Caregiving an elderly parent is also an emotional exercise where the memory of someone who once was very different than they are now and so many of the qualities that made them who you remember seem to have receded.

The other problem with thinking that euthanasia is all right because it alleviates suffering is, at least according to Buddhism, that it cannot. In Buddhism the cycle of birth and death is wrought with suffering. Buddhism teaches the uncomfortable realty that suffering is a part of life. Attachment brings suffering. We feel this intuitively as part of the human experience. We grieve most deeply when we have loved most deeply. Parents worry for their children from the moment they are born.

The goal, in recognizing this suffering in Buddhism is not to eliminate suffering through external control, but to cultivate awareness and compassion within it. To take life to end pain confuses the symptom for the cause; the root cause, attachment and ignorance, remains untouched. The cycle of birth and life is called samsara. There is only one escape from suffering from cycle of samsara and that is enlightenment.

Viewed this way, ending an animals life does not end their journey through samsara or their suffering. At least in being with a beloved pet through the end of its life, it has you as a comfort.

Perhaps there are alternatives. The process of dying can be painful but suffering can be alleviated through palliative care. In Buddhist ethics, there is also a difference between refraining from killing and engaging in extraordinary measures to prolong life. Allowing a natural death with comfort care aligns with non-harming, while actively ending life does not. As much as there is a hospice for humans, perhaps there can be pain medications or palliative drugs to relieve the pain of a suffering animal.

Cultural mores are also shifting with regard to pets. In the past, many people kept dogs outside and viewed them as tools or possessions. Now younger generations view their pets as family members and they themselves as guardians. There has been a marked increase in the number of households that have dogs and cats. People are also spending more money on their pets than ever before. Veterinary care for geriatric pets including rehabilitation, and tools like wheelchairs, is increasingly mainstream.

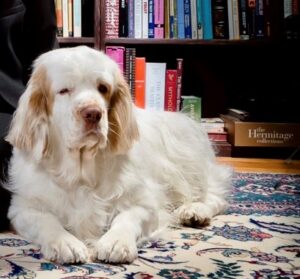

In this context, taking care of my almost 14-year-old dog, Jackson, is a gift I can give him. It is my heart speaking. Similarly, as difficult as it is to take care of my mother, it is also a gift that I can give her from my heart. I know she is getting the best care and it is a relief knowing that when the times comes, I will have done my best by her. There is a sweetness in old age that reminds me of the sweetness of children. It is a privilege to see.

One of the most traumatic things about taking a 14-year-old dog to the vet as a Buddhist is the judgment and unsolicited advice I have sometimes encountered about “quality of life” and the very real question to which I have no answer, that things like arthritis and other chronic conditions will continue to affect him, and that perhaps there may be other things going on.

It is inarguable that there is a fragility to a large-breed dog that has already outlived the breed’s standard lifespan. Will he get better? He will never be 3, or 8 or even 11 again. Aging is a stripping away of vitality and function that is undeniable and universal. So what is the point in doggedly bringing in an almost 14-year-old dog to a specialty clinic, who needs something fixed knowing full well his mobility is impaired and he will continue to age against the backdrop of everything age has brought him?

The conversations and unsolicited advice I have received are few and far between and have come from extremely well-meaning professionals. They could not have known that what is proposed is violently opposed to my religious beliefs. I was first told to put my almost 14-year-old dog to sleep when he acquired blasto and could not breath many years ago. His chances of survival were extremely low. I knew though he was a fighter and thanks to the best veterinary care in the country, he survived and lived many wonderful and active years after this including earning several breed firsts in multiple dog sports. We were fortunate to have met incredible veterinarians and techs, who fought as hard as Jackson did.

But there are those who would say that what I am doing now is to avoid the pain losing Jackson would cause me-that it is selfish. It is certainly true that, on that day, I will feel I will break when I lose him. I am afraid of this pain and there is no precept or belief that changes this dread.

I know this because I have lived it once before. Jackson’s late sister, Star, taught me what it means to say goodbye without saying it. She had inoperable lung cancer, and one morning, she refused to eat. I knew then that it was her last day. I hugged her and told her she had nothing to fear, that it had been the greatest joy and privilege of my life to be her mom. I told her that I would never tell her to go, because I couldn’t, but that if she had to, I would understand, and that she would be all right. I told her I would miss her forever. Then I said I would be right back, that I was just going to get my coat to take her to the vet, in case there was anything that could be done. In the twenty seconds I was gone, she had passed.

Her timing felt like grace. I think she waited until she knew she was loved and safe enough to let go. It reminded me that sometimes, life itself decides the moment, not us.

Watching age change Jackson is similar to seeing how Alzheimer’s took my father away. My dad was a professor and a father figure to hundreds of young people whose lives he impacted for the good. The cruel things about Alzheimer’s for him was that it was his mind that defined him. The disease made him disappear over 7 years. And despite the time I saw the changes it enacted in him, it did not blunt my sorrow when he actually died. The finality is awful. Seeing the decline of a dog or parent because of age and time is the witnessing a slower death. If you are there, it is not an escape or avoidance of pain but very much a choice to be in the same room and stay there.

I once chastised my mother’s oncologist and told him to look beyond her age and not withhold treatment based on her age. To her, she valued her life. Albeit it is a different life than the one she lived as a teacher and traveler. A once fiercely independent woman who wrote and published two books from major university presses. But it is a life filled with moments of joy in things like getting ice cream or Crab Rangoon with dinner. It is a moment where she smiles at seeing her daughter and knows she is never alone in her own home.

With age, the metrics of quality of life change. There is a standard quality of life metric that measures whether a dog can get up and come to greet you. This is a death sentence for dogs with arthritis. But should it be?

Perhaps quality of life should not be measured by mobility or productivity, but by the capacity for comfort, connection, and moments of joy. In both humans and animals, awareness, affection, and peace of mind can remain even as physical function declines.

Should the measures of what someone, a dog or parent can do be static over time, or should there be a metric that takes into account the fact that productivity and functionality change with time, in the course of most every life?

In old age, moments are incredible and can hold immense happiness and meaning. No one knows better the measure of these moments than those who are in the room to experience them. For my mother, it is the simplest things. For my dog, it is a happiness he conveys about simple quieter things that are shared with his mom and the comfort that he is coddled, comfortable and loved.

It is my hope that in time, we will change the metric of quality of life in veterinary care enough to recognize that even if not worn on a sleeve, a person can have deeply held religious beliefs that affect something so universally accepted as euthanasia.

And more practically, that palliative care can be offered more often, because no one knows better what is in the best interests of a pet than the person who is in the room with them every day, in their home. To accompany rather than to terminate, to stay present rather than turn away, this is, in many ways, the living expression of the first precept. It honors the continuity of life and death, and it transforms caregiving into practice itself.

R Tamara de Silva